UCNEGOLD posted this article by a Historical Archeologist, H. Charles Beil, that debunked many of the claims in the stories. My only complaint is i wish he would have included more citations for his research, but i'm sure if one reached out to him, he could provide them. Also note, it appears he was unaware of the "Lost Gold Ingot Treasure" from approx. 1965, that appears in the FBI file, of which the two later stories closely mirror. I've copy and pasted it below and here is the link:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/bank...fKTuU4VIkL9ChNNLLz6MXoAloExOGR3p0YfPaCQH5qHfk

Bank it or Bust it? An Examination of the Dents Run Gold Treasure Legend

H. Charles Beil Author of the "Death Marks the Spot" book series. Historical Archaeologist, Treasure Hunter, Educator, Owner of Treasure Illustrated, and Speaker. Published Aug 5, 2018

Early in 2018 a dozen FBI agents and a treasure hunting group called Finders Keepers went searching for gold ingots in the mountains of Pennsylvania wasting hundreds of thousands of dollars looking for something that never existed. A little research could have prevented this fiasco.

In 1973 an article entitled 26 Missing Pennsylvania Gold Ingots by Sandra Gardner appeared in Treasure Magazine, a magazine that featured treasure stories from around the world. This story has set hundreds and possibly thousands of treasure hunters on a wild goose chase for a treasure that never existed.

I'll recount the story here and then examine its validity and how the story has changed over the years.

"With today’s gold market the way it is, it would be a dream come true for the lucky person who was [to find] this treasure trove. The government reportedly, will give the finder ten percent, and the finder will most likely pay tax on that.

Some believe that the shipment was stolen and the bars divided because at one time, half an ingot was found according to one of the many varying stories about it.

In 1863, Lee’s army invaded Pennsylvania. This movement ultimately led to the historical battle at Gettysburg’s in south-central Pennsylvania, near the Maryland border just off Route 15 in Adams County.

Early in June of 1864 two covered freight wagons, with four mules each, and a small ambulance wagon came from the west and headed north to avoid the Confederate infiltrators. They were bound for the Philadelphia Mint and were to go as far as Williamsport on an overland route. The party was made up of three drivers and eight men on horseback. In the two freight wagons were 26 bars of partly refined gold, painted black and weighing fifty pounds each. Today’s value at $900 an ounce, one of the twenty-six bars would we worth about $630,000.00 or a grand total of $16,380,000.00.

[1. By 1864 Lee's Army had been defeated at Gettysburg and there were no Confederates in Pennsylvania.]

[2. $900 an ounce was not the value of gold in 1973. It was about $72 an ounce.]

Lieutenant Castleton, born of a famous military family, was in command. His fighting career stopped by an acute case of malaria and a hip wound, and he was a bitter and frustrated man as a result.

[3. Lt. Castleton cannot be found in any archive records of any kind; Military, genealogical, US Census, Death records There are 3,000 census records available for the last name Castleton none of which refer to a Lt. Castleton of any other Castleton that was a distinguished military family!]

Sergeant Mike O’Rourke, an undesirable, wanted by the police for many river port brawls involving murders, was chosen for his natural talent for leading and his and ability to be shrewd-talents that were lacking in Castleton.

[4. Sgt Mike O'Rourke cannot be found in any archive records of any kind; Military, genealogical, US Census, Death records. If a military Sgt was wanted by the police he would have been easily arrested and court-martialed.]

Conners, the only other man identified, was mean, unfriendly and sullen. He had been wounded in combat and assigned to limited service.

[5. Connors cannot be found in any archive records of any kind; Military, genealogical, US Census, Death records.]

Three days after coming upon a clearing on the old Clarion River Trail where they had camped, they again camped in a clearing near Ridgway. Arriving in town, Castleton and O’Rourke found the people of Ridgway very hostile and abusive. Castleton tried, unsuccessfully, to buy some Peruvian bark or quinine for his fever which was bothering him more and more.

[6. No validity in this. Ridgway is the County Seat of Elk County and well developed at this time.]

In a tavern, the two men were accused of being drafter’s intent on recruiting men of Ridgway for duty. A brawl, probably instigated by the rough neck O’Rourke, ensured and the two felt fortunate to leave with their lives.

[7. Elk County is home to one of the best Civil War regiments the bucktails and great pride was taken in this and in enlistments. There are no news accounts of this incident. It is purely a fabrication.]

Early the next day the group carefully skirted the town and followed a road heading east, much the same as present-day Route 120. They arrived two days later at St. Mary’s. Here they came in possession of a map of the “Wild Cat Country,” made in 1842 by surveyors, that showed a possible road branching to the south about ten miles east of St. Mary’s and one mile west of the village of Truman (which may or may not have been in existence at that time.)

[8. No such map exists. A military expedition would have had their own maps and plenty of good and reliable maps existed in 1865 of this entire area.]

Today this road is little more than a jeep trail. It crosses two mountains with elevations of 2000 feet, with the west branch of Hicks Run in between, joins an unimproved dirt road just over the summit of the second mountain and here branches off into three directions. Each road, eventually, brings you to the Sinnemahoning River at different points. The road the soldiers were to have taken would have brought them to Hicks place on the same river.

[9. These “jeep trails” are modern 20th century logging roads that were not in existence in 1864.]

[10. This place name of Hicks Run did not exist until 1903 when John DuBois built his lumber camp there. It was known prior as 3 Mouth Run.]

The three-way branch-off was not shown on the soldiers’ map and after trying two wrong choices (to reach the Hicks place), they impatiently headed south through the timber. Detouring around swamps and rocky areas, they became hopelessly lost.

[11. It was not possible to traverse this steep terrain through the timber, boulders, mountain laurel and streams with wagons. Military wagons of this period are known to easily get bogged in dirt and mud.]

Since Castleton was growing much weaker from the fever, and the other men were quarrelsome and exhausted, they decided that two men should accompany Conners and start southeast toward Sinnemahoning, on foot to get help. Meanwhile Castleton and five other men were transferring the gold from the freight wagons to pack saddles made from the canvas wagon covers, so the mule team could start south as fast as Castleton’s condition would permit. At this point the group was on the ridge going north and south just west of the east branch of Hicks Run.

[12. The FBI was searching for the gold in the area of Dents Run several miles away.]

Castleton gave Conner a report of the trip and a Federal Army order so Conner's could requisition supplies and men for help. Later Conner's said that when he left. O’Rourke and Castleton were arguing over whether to bury part of the gold or to try to carry it all. No more was ever seen of the group.

[13. Arguing with a Superior Officer is an act of insubordination that was seriously dealt with in this time. O'Rourke could have been executed for this so it's highly unlikely this happened.]

Conners, arriving ten days later with a rescue party from the Lock Haven Post, found the abandoned wagons. It was apparent that the group had split up as there were several trails to the southwest. The rescue party searched for several days before returning to Lock Haven.

[14. There was no Lock Haven post in 1864 and no account of this in the historical record.]

A court of Inquiry, held at Clearfield, Pennsylvania, charged Castleton and O’Rourke with treason and theft. The charges were dropped, pending further investigation, as Castleton’s family had much influence high in army circles.

[15. No record of this in the Clearfield County Courts. Why would you prosecute men who were lost and presumed dead?]

In an attempt to keep the natives from searching for the fold, the Pinkerton Detective Agency convinced the War Department that the utmost secrecy was desirable. Several teams of Pinkertons posed as prospectors and lumbermen in the area, alert for any signs of sudden wealth, and asked discreet questions. The area they thoroughly searched was from the Driftwood Branch to Benezette Branch of the Sinnemahoning River as far west as St. Mary’s.

[16. No record of this exists in the Pinkerton Archives.]

Two summers later, in 1865, Donavan and Dugan, detectives, found two and one-half bars of the gold buried under a pine stump about four miles south of where the wagons were abandoned. This indicated that the treasure had been stolen and divided.

[17. No record of this detective agency can be found in any archive.]

[18. Finding bars of gold is extremely unlikely without the use of modern electronics and knowing in which direction the men headed. There is nothing in the historical record that states any gold was found.]

These same detectives came to love this wild country and in 1871, eight years later when the search ended, they retired from the agency. They built a cabin north of Benezette, on Trout Run, and occasionally searched on their own for the treasure.

[19. There is nothing in the tax records that shows land ownership by these men]

In 1866, a year after the gold bars were discovered, a pair of the mules was found by other Pinkerton men. The mules still carrying the army brand were in the possession of an old man in Chase Run. He said that he’d found them wandering in the woods. Then in 1876 the Elk-Cameron boundary was being resurveyed. The survey crew found the bones of from three to five human skeletons scattered around near a spring at the head of Bell’s Branch of Dents Run approximately seven miles from where the wagons had been abandoned. Nothing more is known of the gold or the men, but the government is still looking!

[20. Pinkerton has no record of any of their detectives finding army mules.]

[21. There is no record or newspaper account of skeletons being found]

Anyone interested in searching for this long-lost treasure should equip himself with the Benezette fifteen-minute series topographical map, a good four-wheel-drive vehicle, a metal detector and perhaps a mule or two. A good snakebite kit should also be included because this area is heavily populated with rattlesnakes!"

Now I'll compare this story to the story by Francis X Scully that the Finders Keepers Treasure Hunting Group who is involved in the search for this gold with the FBI references on their website.

PENNSYLVANIA’S LOST GOLD INGOTS

by Frances X. Scully

[22. Frances X. Scully is a writer who is well known to have plagiarized Henry Shoemakers works and added phony treasures into them.]

A tremendous treasure is lost somewhere in the heart of Pennsylvania’s Elk-Cameron County. During the Civil War, a shipment of gold bars worth over $1,500,000 at present market prices disappeared somewhere in the mountainous area. It has never been found.

[23. Discrepancy in the value of the gold from 1973 story.]

The gold, 26 bars weighing 50 pounds each, won’t be easy to track down. North-central Pennsylvania is still a rugged, untamed region that contains the largest elk herd east of the Rocky Mountains, If you hunt the treasure during the mating season, you could be kept awake nights by the bugling of the monstrous bull elks. During the day, watch for the crotalus horridus, better known as the banded timber rattlesnake. You could bump into one anywhere, just waiting for an unwary arm or leg.

[24. In 1750 the weights and measures standard is 400 ounces or approximately 25 lbs]

At the start of the Civil War, northern Pennsylvania was as remote as northern Quebec, Canada, is today. Known as the Wildcat Region, this area led the entire world in lumber production. Immense rafts were floated down the narrow valleys to great sawmills. There were few roads and only a handful of pitifully small villages. Howling wolves were heard at night and panthers and bears were common. Rattlesnakes and copperheads were as thick as flies at a picnic.

[25. In 1863Pennsylvania was well developed with roads, towns and even a railroad in the area of Dents Run that was built in 1859. These statements of the conditions in Pennsylvania are completely false.]

This was no place for choir boys. During the Civil War, the Wildcat Region, was the birthplace of the famous Bucktail Regiment, those hardy men were the scourge of the Confederacy. Following the defeat of the Union Army at Chancellorsville, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee pointed his conquering gray legions toward Pennsylvania’s lush farmlands.. The North was in bedlam as Philadelphia and Harrisburg prepared feverishly to resist the invasion. Pennsylvania’s Governor Curtin felt the situation was so serious that he asked the Union commander, Gen. Meade, to send Gen. Couth to defend Harrisburg, the state capital.

Meanwhile, a young blue-coated lieutenant headed northward from Wheeling, West Virginia, with a wagon with a false bottom, a civilian guide and a guard of eight cavalrymen. The boyish officer was stunned when his orders revealed what his cargo was. He shook his head in disbelief, reading that he was to proceed as far north as necessary to avoid any possibility of bumping into Rebel patrols, then turn southward and head for Washington. He was by all means to avoid contact with the enemy.

[26. One wagon versus 3 wagons in Gardner's story.]

[27. Scully places the story in 1863 while the Gardner story places it in 1864.]

His freight was pure gold, stored beneath the false bottom of the wagon, which was covered with hay.

[28. Gardner states that it was unrefined. Pure gold bars would have been created following the 1750 mint specifications.]

His superiors cautioned the young officer that Pennsylvania was infested with another type of copperhead besides those that crawled along ground—the underground organization of Southern sympathizers. His was an important mission and he must never relinquish his vigilance. The army was certain they had selected the right man for the task along with a fine squad of riders and a superb civilian guide. Time was to prove the army wrong.

[29. The Civil War Copperheads never attacked anyone. They were a political organization of Southern sympathizers only.]

[30. Connors is not a civilian in Gardner's story.]

So the expedition headed northward. It is believed they stopped first at the town of Butler, then a thriving lumbering community north of Pittsburgh. Almost from the start, the young lieutenant was seized with one fever after another and had to ride in the wagon. While the officer was ill, the civilian guide took command.

[31. This is not likely. This was a military expedition and the chain of command would have been strictly followed.]

The caravan continued northward through Clarion Valley, where eastern bison had grazed 75 years before.

When the expedition reached the town of Clarion, the pale and wan officer resumed command. Feeling they were far enough north to avoid contact with Rebel cavalry, he decided to head northwestward to Ridgway, then eastward to the Sinnemahoning River near the town of Driftwood. There, they could easily construct a raft and float down to the Susquehanna River, then on to Harrisburg, putting them much nearer Washington.

[32. Ridgway is Northeast of Clarion and not Northwest. Directions are backwards.]

[33. According to Gardner their orders were to go to Williamsport. They would not have deviated from their orders.]

So far the journey had been uneventful, though the young soldiers were puzzled by being so far away from the scene of action. They wondered what was in the wagon. Oh, well—the army was known for doing strange things. How about the ‘Mud March’ last winter, when 70,000 troops were stuck in the mud? How the Southern newspapers had howled over that.

On a Saturday night in late June, the expedition pulled into Ridgway in Elk County. The little band of soldiers were as welcome as tax collectors and the populace swarmed all over the troopers. Several times the lieutenant had to order the jeering crowd to disperse. The puzzled officer asked the civilian guide if Ridgway hadn’t produced the Elk County Rifles, one of the best companies in the Bucktail Regiment. When informed that indeed it had, the young officer was stunned by the hostility of the crowd.

[34. Scully sensationalizes Gardner’s story here. There is no mention of this in the Ridgway newspaper]

That night the caravan headed off through the darkness toward the little Dutch community of St. Marys, 11 miles to the east. During the night the lieutenant had another severe seizure. In his delirium he cried out a complete disclosure of the gold and the purpose of their mission. The escorting soldiers were stunned.

[35. St. Marys was a large thriving community at this time.]

[36. No diaries of these men exist so how do we know the minute particulars of what they experienced? This is all fabricated. These are patently false statements that cannot possibly be known without a journal or some type of written testimony.]

Meanwhile Connors, the civilian guide, once more assumed command. After an evening in St. Marys, where the patrol was reportedly treated like conquering heroes, Connors announced that the expedition would head over the mountains toward Driftwood and the headwaters of the Susquehanna. They were just 20 miles from their goal, but it would be rugged going.

[37. There is a chain of Command in the Military and no civilian would ever be permitted to assume command over a military operation!]

The group left St. Marys—and that was the last anyone ever saw of the ill-fated expedition. In August, a wild-eyed hysterical Connors staggered into the village of Lock Haven about 40 miles east of Driftwood. He told a pitiful story of the death of every member of the expedition and the loss of the entire cargo.

[38. In Gardner's story Connor left the group with 2 other men and returned with help.]

The kind citizens were overwhelmed with sympathy for the hollow cheeked Irishman. The Wildcat Region was no place to be lost in, they agreed. Rattlesnakes, copperheads, mosquitoes, wolves, panthers—all were hazards, and besides, they were guarding a wagon filled with gold. Who could have ordered such a crazy move, wondered the people of Lock Haven.

[39. No record of this in the Lock Haven newspaper]

While the local residents believed Connors, the army did not. They put him through a relentless series of questionings. First Connors told of the officer dying and being buried, and then he told of a terrific fight. After that, he;always claimed that he lost his memory.

[40. There is no record of this legal inquiry in any military record.]

[41 Scully contradicts Gardner's story]

The army brass turned the case over to the Pinkertons. For a time the forest wilderness swarmed with agents, who hired on as lumberjacks, teamsters: or whatever else was available. They searched the area of almost a year, but with no success.

[42. There is no record of this in the Pinkerton Archives]

During the summer some dead mules were found—perhaps the ones that pulled the wagon. From somewhere, an aged recluse had managed to get hold of horse trappings marked with the U.S. Army insignia, but he wasn’t telling anything to anyone. Two or three years later, several human skeletons, believed to be those of the guards detail, were found in the Dent’s Run area of Elk County not far from Driftwood.

[43. Scully contradicts Gardner's story that a man found the mules alive.]

Connors was inducted into the army and transferred to a western outpost. He was never permitted to be discharged. When drunk he would blabber that he knew the whole story about the gold and offer to lead someone to it. But when sober he couldn’t even find Elk County on the map.

[44. Fabricated, the military cannot hold an individual indefinitely.]

[45. The US Army hired a "Guide" that can't even find Elk County on a Map. Highly likely.]

There are stories that the government reopened the case within the last 30 years and sent agents to the area, but very little information on this was disclosed. In fact, very little information exists on the puzzling expedition itself.

[46. The US government has No record of this.]

Until about 25 years ago, articles about the gold appeared occasionally. A short time ago, a St. Marys man came to me with some pieces of cherrywood taken from a big square bedpost. The bed was found in a home in Caledonia, a small town about 13 miles southeast of St. Marys. Many believed the treasure was lost near Caledonia. The finder thinks the message written on the pieces wood and then nailed to the top of the bed had something to do with the treasure.

[47. There are no articles in any newspaper up to 1963 about any gold being lost at Dents Run or even in the entire state of Pennsylvania.]

The message is written in the type of penmanship used in the 1860’s, and it mentions the year 1863. It also mentions a two-hour battle near a "big rock," and the mysterious writes says that "they see me."

[48. Fabrication by Scully, contradicts Gardner's story that states events took place in 1864]

There has always been a theory that the little band was ambushed and massacred by Copperheads or a Gang of robbers. Many feel that Connors may have planned arch an ambush. Perhaps the mysterious message about a battle is factual.

[49. This is completely fabricated by Scully. There is no historical or factual basis for this comment.]

Meanwhile, $1,500,000 in gold remains lost somewhere in the mountains. Hundreds have looked for it and found nothing. But it is believed to be still there.

Conclusions

So what we have are the only two accountings of this story that offer considerable contradictions to each other in the details of this legend.

Since the story written by Susan Gardner predates that of Francis Scully by at least 20 years (Note: this claim appears to be incorrect, the Gardner story predates the Scully story by about one year) it is to be supposed that Scully took his information from Gardner's story and then further embellished it to suit his needs. As such we cannot consider Scully's work as even a tertiary source of history. It contains no valid facts and doesn't even faithfully reproduce Gardner's story. Scully's legend is then just that; a fictional legend and not anything that you would base a treasure hunting expedition on. Francis Scully is well known for plagiarizing the works of Henry Shoemaker and inserting treasures into them where none ever existed.

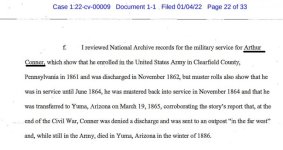

In my examination of the US National Archives, which contains records on every man who was in the military and fought in the Civil War none of the three principle people mentioned in the legend; Castleton, O'Rourke or Connor are to be found. More simply put, these men were never in the Army. Further research in genealogical databases of the Latter Day Saints (largest genealogical database in the world), US Census reports and death indexes also failed to find anyone who fit the descriptions of these 3 men. These three are fictional characters that were created by Susan Gardner.

Another way I debunked and dated this treasure legend is through the use of weights, measures and time tables. I examined the quantity of gold as detailed in the legend; 26 bars weighing 50lbs each. These bars had a total weight of 1,300 lbs. While this sounds like a considerable amount of gold, it isn't. 1 cubic foot of gold weighs approximately 1,250 lbs. So you see, it wasn't like there were gold bars lining the bottom of a wagon. Physically it is a very small amount of gold. Monetarily, the legend claims that the gold was worth $1,500.000. This is interesting because in 1863 gold was $31.23 and in 1864 gold was valued at 47.02. In neither year was the gold worth 1.5 million dollars. To determine its value we only need to look at the historical value of gold and multiply it by the number of troy ounces in the legend.